The Ukrainian Catholic Church – The Union of Brest

A Historical Overview 1596 - 2001

Bishop Roman Danylak, J.U.D., D. D.

originally published by Catholic Insight

updated October 2001

Historical background

The Ukrainian Catholic Church was again drawn into the limelight with the celebrations in 1996 of the 400th anniversary of the Union of Brest (1596), and the 350th anniversary of the Union of Uzhorod. The celebrations of our Catholicity as the Ukrainian Catholic Church, a particular Church in the universal Catholic Church, of the Byzantine Ukrainian rite, are evoking mixed reactions both without as well as within the Catholic Church. At stake are opposing views of the unity willed by Christ for His Church.

The Catholic view

The Ukrainian Catholic Church, as it now exists, reflects the ecclesiology of the Church as the one body of Christ, established on the rock of Peter, and submitted to the universal ministry of charity to his successors, the Popes, by the will of the Divine Founder. It embraces the union of a variety of particular Churches which continue to follow the religious, spiritual, theological, and disciplinary patrimonies inherited from early Christianity.

Following Vatican Council II the term "Local Church" has a twofold meaning. Primarily it refers to the basic Local Church, what is today called an eparchy or diocese, committed to the care of a bishop. In this primary sense the Local Church is a constituent element of the universal Church; it belongs to the very essence of the church. St.. Paul addresses the local churches in Rome, Ephesus, Corinth, etc. We have inherited the canonical and theological traditions of antiquity, in the ecumenical and topical or local councils of the Church.

But the term is local and particular is also applied to the Patriarchal churches. The Ukrainian Catholic Church, sometimes called the Kievan church, after its Metropolitan See in the city of Kiev, Ukraine, is one of those patriarchal or archiepiscopal churches which enculturated the Gospel faith of Christ in the Slavic language and the liturgy of Constantinople, the seat of the Eastern Roman Empire (which lasted till 1452) and the see of the Patriarch of Constantinople.

Vatican Council II in its Decree on the Eastern Catholic Church describes the mystery of the Church thus:

"The holy and

catholic Church, which is the mystical body of Christ, is composed of the

faithful, who are organically united in the Holy Spirit by the same faith, by

the same sacraments, and by the same government. These, joined into a variety

of groups, constitute the particular churches and rites. There is a marvelous

communion among them, in which the diversity of the church does not affect its

unity, but rather manifests it..." (Decree on Eastern Catholic Churches,

n. 2).

The Orthodox view

Another view is that of the Orthodox Churches of the East. They do not accept the primacy of the Pope and are not in union with Rome. They hold that the one Body of Christ resides in the family of apostolic Christian churches joined by spiritual and mystical ties. Because they are geographically based, they regard the entire East as rightfully falling under their exclusive domain. They complain, for example, about the Roman or Latin rite Church setting up dioceses in Eastern Europe, the Eastern Balkans (Rumania, Bulgaria, etc.), and the far-flung Russian union of states. Rome has gone ahead, nevertheless, on the straightforward ground that Latin rite Catholics are now living throughout these regions and have a right to its ministry. Needless to say, the Orthodox churches are even more upset about the evangelical Protestant sects which have attracted a large following throughout Russia.

The Orthodox churches, especially the one in Moscow, also oppose the existence of the Ukrainian Catholic Church, which is sometimes called a "Uniate Church," having re-joined the Latin church by an official treaty of Union in 1596.

Two current expounders of this theory are the present patriarchs of Constantinople and Moscow, Bartholomew I and Alexius II. In recent interviews reported in the magazine 30 Days, Alexius II rejects the so-called 'uniatism' of the Ukrainian Catholic Church (30 Days, 1995). And the recent ecumenical encounter of Balamand drafted certain ecumenical principles which I will consider in Part II of this article.

How did "uniatism" develop?

The history of the Ukrainian Catholic Church is intimately connected with the social and political history and destiny of the Ukrainian people. Its origins must be traced back to the dim beginnings of Christianity in Ukraine. Legendary tradition has it that the first-called of the apostles, Andrew, was the first to erect the cross of Christ on the hills of Kiev. Be that as it may, there is no question that Christian communities flourished around the shores of the Black Sea in the first centuries of the Christian era. The veneration of Pope St. Clement, martyred at the end of the first century, was well established in this area. We also have documentary evidence of the presence of Arian communities in this basin north of the Black Sea, in the fourth and fifth centuries. There were organised Christian communities with their own bishops, along the southern shores of Crimea.

But it is not until the eighth century that we can determine with some certainty the penetration of Christianity into the lands of Rus-Ukraine. The Apostles of the Slavs, Cyril and Methodius, were in Crimea in the mid-ninth century. There is evidence that St. Methodius and his disciples penetrated the lands east of the Balkans with their missions. Some authors claim that they also established the dioceses of PeremyshI and Cracow a hundred years before St. Volodymyr.

When Olga, widow of Prince Ihor Rurik and regent for her son Sviatoslav, willed to be baptized in 955, the Christian faith must have been showing healthy signs of life in the capital of the Rus empire. The 'baptism of Ukraine' under St. Volodymyr in 988(9) was the culmination of the progressive evangelization that had thoroughly penetrated to the roots of Rus-Ukrainian culture.

Kiev, a new hierarchy

With his conversion and baptism, the Grand Prince Volodymyr gave official impetus to this movement, establishing hundreds of churches, monasteries, and religious institutions. Before his death in 1015, Kiev was in its glory as the city of churches. Religious life continued to flourish in the Kievan capital and to expand its missionary influence throughout the entire realm of the Grand Principate of Kiev - to the north, into the duchies of Novhorod, Suzdal, and Moscow; and westward, to Halych, Lviv, and PeremyshI.

With the reception of Christianity, Volodymyr provided an established a hierarchy for this new church, united under the jurisdiction of the metropolitan of Kiev. Jaroslav the Wise, son and successor of Volodymyr, provided for the election of the first indigenous metropolitan, Hilarion, in 1050, establishing by this act the autonomy of the Ruthenian or Ukrainian Church in the Kievan metropolitanate from the political and ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Byzantium.

At this time Byzantium had not yet ruptured ties with Rome. Kiev had received the Christian faith as a part of the Catholic Church. And even following the unfortunate schism of 1054, the grand princes and metropolitans of Kiev continued in communion with Rome for almost a century. The devotion of Yaropolk to the See of Peter, and the introduction of the feast of the Translation of the Relics of St. Nicholas to Bari in Italy in 1087, are incontrovertible evidence of the continuing ties between Kiev and Rome.

The Tartar invasion

With the Tartar

incursions and civil strife among the contending princes of Rus, the subsequent

religious picture of Ukraine remains obscure to historians. The ensuing turmoil

compelled Metropolitan Maxim to flee to Volodymyr on the river Kliazma in 1299.

In 1325 his successor, Peter, confirmed as metropolitan of Kiev and all Rus by

the patriarch of Constantinople, established permanent residence in Moscow -

which was to prove a sorry decision for subsequent history. It was in this

period that the metropolitan see of Halych was established (1141-1371). This

see would be restored centuries later for the Ukrainian Catholics of western

Ukraine.

Council of Florence

It is only in the middle of the fifteenth century, with the union of the Council of Florence in 1439 and its proclamation in Kiev and all Rus by Cardinal Isidore, that the historical picture is clarified. In 1457 Kiev was confirmed as the metropolitan see by Patriarch Gregory of Constantinople with the appointment of Gregory, a disciple of Cardinal Isidore, as its metropolitan.

Subsequent political intrigue induced Pope Pius II to confirm the ancient metropolis reestablished in Kiev in 1458 and to confirm Gregory as its metropolitan. But it was not until the Union of Brest-Litovsk in 1596 that Metropolitan Rahoza of Kiev and his suffragan bishops gathered in synod could clearly express the muted desire of the Ukrainian people to cement their communion with the See of Peter.

Dissension

Unfortunately, inner dissension, the political ambitions of the Ukrainian nobility, and the relentless political incursions of Russia and Poland did not promise lasting success to the heroic efforts of these saintly bishops, especially since the dissenting opposition had convoked an anti-synod. The Greek Patriarch Teofan of Antioch consecrated Job Boretsky as Orthodox metropolitan of Kiev in 1620. But the idea of unity did not die even within the reconstituted Orthodox Church.

As Ukraine was parcelled out to new political masters, Russia, Poland, and Austria, the unity was torn and destroyed. In 1685 the dissident bishop of Lutsk, Gedeon Chetvertynsky, submitted himself to the patriarchate of Moscow and was designated metropolitan of Kiev. So Kiev became a prisoner of Moscow. The Catholic metropolitan see in the new Russian empire was ultimately suppressed in 1805 with the death of the last Kievan metropolitan, Theodosius Rostotsky.

Notwithstanding the good will of Tsar Paul I (1796 - 1801) and the few feeble attempts of the remaining Ukrainian Catholic Bishops to maintain themselves in existence, the church was unable to withstand much longer the continued harassment from the tsars. Finally, through a succession of 'ukazes' (decrees), Nicholas I dealt the death blow to the Union in eastern Ukraine with the surrender in 1838 of three bishops who had betrayed their Church. The idea of Union in eastern Ukraine was finally destroyed.

Western Ukraine

Divine Providence had already provided for the continuation of the idea of the Ukrainian Catholic Church, however, in areas not under Tsarist control. The Union was established in the lands of Transcarpathia in 1646. Although the bishops of Lviv and PeremyshI in Galicia recanted their initial acceptance of the Act of Union of 1596, a century later Bishop Innocent Wynnytsky of PeremyshI declared himself a Catholic in 1692 and brought with him his entire flock. Bishop Joseph Shumlansky of Lviv did the same in 1700. Bishop Dionysius Zhabrotsky of Lutsk adhered to union in 1702.

Refuge in Austria

As mentioned, the Catholic metropolitanate of Kiev was suppressed by Moscow in 1805. In response to this act Pope Pius VII re-established the metropolia of Halych in 1807 in the Austrian domains, and conferred upon its titulars all the rights, dignity, and prerogatives of the metropolitans of Kiev. He recognized the metropolitan of Lviv-Halych as head not only of the ecclesiastical province of Halych, but of the entire Ukrainian Catholic Church. This quasi-patriarchal authority was confirmed in the recognition by the Holy See of Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj as Major Archbishop in 1963, according to the prescripts of eastern canon law (promulgated in the Motu Proprio Cleri Sanctitati in 1958, canons 324 and 332).

A new hierarchy overseas

Economic and political oppression at the end of the 19th century and the ravages of World War I forced many Ukrainians to leave their homeland. They sought refuge in Canada and the United States, in South America and the countries of Western Europe.

Through the pastoral efforts of Metropolitan Andrew Sheptytsky (1865-1944), the great servant of God who heroically pastured his flock in his homeland and pursued his people throughout the vastness of Ukraine and even Russia and across the oceans, a new hierarchy was established to provide for the spiritual and pastoral needs of these people. They came from Galicia and Transcarpathia in large part, in the years 1890-1914 and 1920-1939 and, finally, after the Second World War.

The first pioneer bishops appointed by the Holy See were Bishop Soter Ortynsky in the U.S.A. and Nicetas Budka in Canada. These new ecclesiastical formations went through their own evolution and were finally established as distinct metropolitan sees in North America and eparchies or exarchates in the other countries of the diaspora, such as Argentina and Brazil.

Persecution and Martyrdom

Metropolitan Andrew died November 1, 1944, during the second Soviet communist occupation of Ukraine (the first one was in 1920). He was succeeded by Archbishop Josyf Slipyj, to whom Divine Providence, together with his fellow bishops - confessors and martyrs - entrusted the awesome task of pastoring the Ukrainian Catholic Church in the underground and throughout the Siberian prisons and labour camps, following the official liquidation of the Ukrainian Catholic Church by Stalin and his emissaries in March-April, 1946.

The heroic deeds of this church of the catacombs are still awaiting their chronicler and historian. Among the numbers of unsung heroes, new martyrs and confessors, of this period between 1946 and 'perestroika' and the ultimate downfall of the Soviet empire in 1990/91, we have come to know one of the chief protagonists of the catacomb church, a layman, Josyp Terelya. Josyp was released from Soviet prisons in February 1987, and sent into exile in the free world, stripped of his civic rights and citizenship, together with his family. He was the chronicler of the activity of the church between 1962 and 1987, and its witness before the conscience of the free world to the present day. (See his book Witness . . . .)

Today

Following his release from prison in January, 1963, Archbishop, later Cardinal, Josyf Slipyj continued his leadership of the Church from his new home in Rome, until his death on September 7, 1984. He was succeeded by his coadjutor Archbishop, now Cardinal, Myroslav Lubachivsky. It was left to him to restore the residential see of Lviv, following the collapse of the Communist empire, and gradually the rights of the Ukrainian Catholic church in Ukraine.

Cardinal Lubachivsky convoked the synod to celebrate the restoration of communion with the Holy See in the forthcoming 400th anniversary of the Act of Union of Brest-Litovsk, and the 350th anniversary of the Union of Uzhorod.

In Ukraine these celebrations began with a national pilgrimage to Zarvanytsia, the home of one of the most renowned miraculous icons of the Mother of God, and the site of reported apparitions of the Blessed Mother in 1987, along with Hrushiw and other famous sites of the intervention of the Mother of God, the Mother of Perpetual Succour, who has sustained the faith of this people in its millennial history as the people of God.

With the return of the Major Archbishop to his archiepiscopal see, the life of the Ukrainian Catholic Church began to return to canonical regularity. Cardinal Lubachivsky convoked several synods in western Ukraine. Following his death in December, 2000, the Synod elected Bishop Lubomyr Husar as the Major Archbishop. Pope John Paul II shortly thereafter elevated him to the cardinal purple.

With the extension by the Holy See of the rights of Ukrainian Catholic

Church to expand its pastoral activities beyond the old borders, the Synod has created new eparchies not only

within the bounds of the Archdiocese of Lviv, but in the last synod in July, 2001

it has created new eparchies in eastern Ukraine.

With the extension by the Holy See of the rights of Ukrainian Catholic

Church to expand its pastoral activities beyond the old borders, the Synod has created new eparchies not only

within the bounds of the Archdiocese of Lviv, but in the last synod in July, 2001

it has created new eparchies in eastern Ukraine.

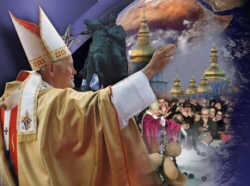

Finally the first pastoral visit of the Holy Father to Ukraine in June, 2001 to the capital of Kiev and Lviv in western Ukraine, the Holy See recognized the vitality of this Church that has survived a century of persecution under Soviet Communism. With the beatification of the bishop and priest martyrs of this Church together with the others, whose sanctity of life was recognized in the act of beatification, the Church has honoured the hundreds of thousands of priests, religious and laity who were the strength and the glory of the Church in the period popularly called the Church of Silence.